THE PROOFREADER’S PLAYBOOK: BUILDING GOOD PROOFING PRACTICES

There’s a secret to good proofreading. You want to know what it is? It’s simple. Good proofreading isn’t an art, it’s a science. Like all scientific endeavours, proofreading should be approached methodically, with easily reproducible steps that one can follow towards a clear result. The result, in this case, is good copy. The steps are what I like to call the ‘Proofreader’s Playbook’.

Fun fact about proofreading to start with. The word isn’t as old as you’d think; its first use can be traced back to only 1845, according to Merriam-Webster at least. It originated in the publishing industry, fittingly enough, stemming from the term ‘galley proof’. A galley proof is a next-to-final copy of a text meant for sign-off or review by the text’s original author, editorial team, or proofreader before going to print. Galley proofs have extra-large margins for the reader to leave notes on errors, inconsistencies, formatting issues, syntax problems, and any other grammatical mishaps that might crop up.

The reason I start with this etymological titbit is to give a firm sense of proofreading’s place in the writing process, and, therefore, establish exactly why I call it a science and not an art.

Proofreading is not copyediting. Copyediting happens during and after the drafting process. Copyeditors comb through arguments and content, finding flaws in logic and incoherence in the flow of a piece. They make suggestions, trim sentences, sometimes even move entire paragraphs around. They’re involved directly in the creative process. Proofreaders don’t do these things. They aren’t here to be creative. Proofreaders are analysts, auditors. They’re calculating and cold and invested only in accuracy. They’re QA warriors and your final line of defence before potentially embarrassing errors see the light of day and undermine your writing in front of a global audience.

I’ve run my share of proof passes over the years. I’ve seen every kind of mistake you can imagine. Let’s be honest, when you’re not involved and can’t be held responsible, they can be pretty great. Everyone can get in on the joke with a good typo and there are so many hilarious examples out there. But when you’re behind the wheel, they’re not so funny. At best, they’re a little embarrassing. At worst, they can cost livelihoods and more money than the GDP of a small country.

Whether you’re writing just for yourself for fun or for a global brand, you want your writing to be on point so you can avoid embarrassing incidents and feel confident in the authority and clarity of your text. That’s where the Proofreader’s Playbook comes in, easy-to-follow steps for casual writers, students, and seasoned wordsmiths alike to help develop concrete proofing practices for content of any kind. Are you ready? Let’s get started.

Step away for a while.

Before you start, stop. Most people don’t have the luxury of sprawling copyediting or proofreading teams. Despite what a lot of people think, most big global brands don’t either. In all likelihood, you’re going to be the one proofreading your own article or essay. If that’s the case, listen up.

Once you finish up your draft and have done a little copyediting, close the document and step away for a bit. Stepping away doesn’t need to be unproductive – go work on something else, catch up on some emails, whatever.

The closer you work on something, the harder it is for you to see it for its constituent parts. You hyperfocus on certain elements that in turn make you blind to others. Taking a little time away allows you to come back refreshed and able to see the forest for the trees.

Read aloud.

This one can be pretty embarrassing, especially if you work in an office situation, but it’s extremely effective. Reading text aloud can help you in two pretty major ways.

First of all, it gives you the advantage of finding out just how naturally your copy flows. Sentences that have you tripping up again and again will probably be difficult for your readers to keep up with too. Identifying these tricky sentences will allow you to craft something that feels a little more natural.

More importantly though, reading a text aloud changes the way you experience it. It builds a barrier between the part of your brain that’s creating something and the part that’s analysing or understanding something and makes them act separately. This added layer between you and your text allows you to experience it differently and therefore find new elements and potential room for improvement that you probably wouldn’t have noticed before.

Weed out redundancies.

Writing is the product of a mind in action. No mind is completely coherent in its every interaction. Our thoughts leave meandering little footprints on the page as we write.

Sometimes the sentences we’re writing change as we’re writing them. This happens because we’re thinking as we’re writing and usually our brains work a lot faster than our fingers do. Or perhaps because we start a sentence, become distracted, and pick up again a few moments later with a slightly different train of thought. When this happens, we can forget to completely reengage with what we’ve written previously and accidentally repeat what we’ve already said – sometimes even within the same sentence.

Other times, we pepper our paragraphs with needless verbs and adjectives to make our prose more flowery or impactful. Sure, this helps show off a wide vocabulary, but if readers wanted to be wowed by new words, they could open a dictionary.

Scan the text closely for repetition and redundancies that might take away from the coherence of the article. They may read just fine, but, by definition, they are unnecessary.

Mark changes and suggestions clearly.

Pretty basic one but crucial not to forget. It doesn’t matter if you’re proofing for yourself or for someone else; while the document is being proofed, mark changes and suggestions clearly. You could even leave notes explaining certain changes if you need to so you remember what they mean when polishing the final draft.

Beyond giving yourself or the reader a clear visual on what’s been changed (just in case it needs to be changed elsewhere, for example), it gives you a reference point for other similar mistakes that could also pop up in the text.

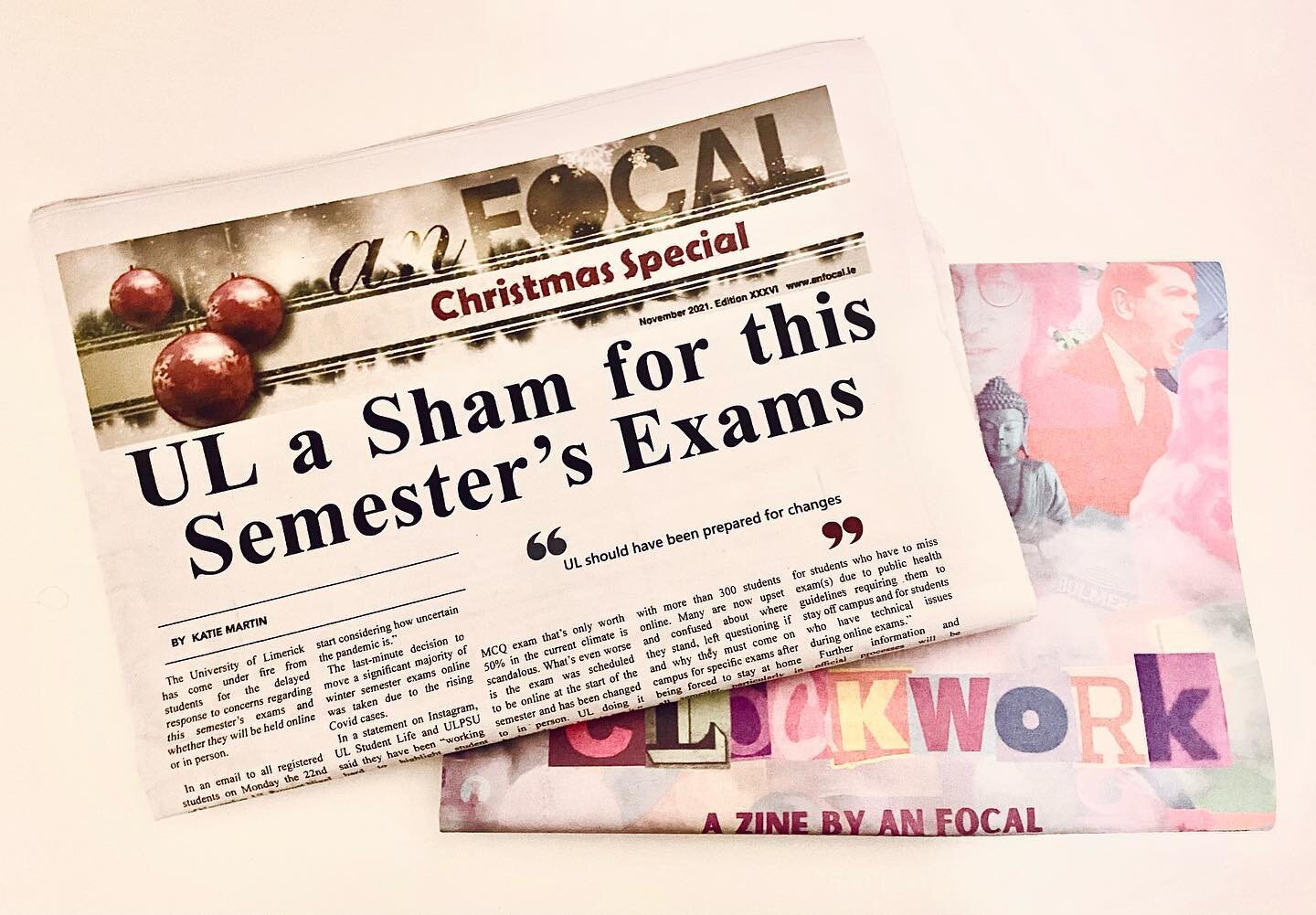

The most common methods of tracking are, funnily enough, ‘track changes’ in Microsoft Word/Google Docs/LibreOffice/Open Office or a simple old red pen (or yellow, or green, whatever floats your boat…).

Check your facts and figures.

If you’re proofreading for someone else, generally facts and figures will be worked out somewhere between the drafting and copyediting phases (if not in preliminary research, ideally). Still, it’s good to do due diligence. If you’re proofing your own text, check, check, and check again.

Never forget to check those facts and figures one last time before they go out to the public, no matter how confident you are in them. Nobody was ever hung for triple checking their facts and figures. Though, now that I say that, I don’t have any data to back that up…

Keep error lists and style guides.

One of the best practices you can learn as a proofreader is to keep regularly-updated reference documentation for the project or file you’re working on. Error lists and style guides are two of the most effective and will keep you organised when everything else around you is chaotic.

Error lists are a real life saver and they couldn’t be easier to make. Have you found a mistake in the text? Note it down in a separate file. You can be as comprehensive or as loose as you like in this. This document is just for you – or your team, if you’re working with a team. The point is to create a working list of common mistakes within a particular text so that when the time comes to give the file the final once over, you have a quick hitlist of potential leftover errors to run through. The better you know what mistakes you’re looking for, the easier a time you’ll have in correcting them. Error lists are especially handy if you’re proofing multiple files within a larger project.

Style guides are a little more all-encompassing. They aren’t just about noting down and referencing common errors. They’re about providing a basis for what the tone and feel of a text should be. Is it supposed to be in UK English or US English? Are there specific words that should be avoided? Should the text use dashes instead of bullets in lists? Should MLA or Chicago style be used for referencing and citations? Your style guide should contain all the information you need to make sure a document is bulletproof, right down to preferred fonts and paragraph spacings.

Keep your error lists and style guides up to date and you’ve already got half the work done each time you open a new document.

Proof at least twice.

I’m going to contradict this one in just a few moments, but let’s consider this an absolute minimum. Nobody ever caught every mistake on the first read-through. Odds are you won’t on the second either. Always aim for at least two passes as a solid rule of thumb. If you’ve got time for another pass, do another pass.

Be consistent.

Consistency errors are some of the most common you’ll find in poorly proofed text. They come in a wide variety of forms from purely linguistic to style and formatting, all of which can really impact the accuracy and flow of a piece of writing.

Maybe the text jumps from justified to left aligned needlessly. Maybe some canon or native terms receive capital letters where they usually wouldn’t because of context – this is very common in video games, for example, where many everyday terms actually refer to in-game items or rewards that the developer wants to highlight or differentiate.

Maybe it’s something simpler, like misused punctuation marks. Writers who learned to type on a typewriter will often leave a double space after a period, which nowadays is totally redundant. Many German-speaking writers or translators will often leave words capitalised unnecessarily when writing in English because the German language has a greater tendency to capitalise nouns. Be aware of these little traps that pop up and catch the wrong kind of attention.

Inconsistent writing takes away from the authority of a text. It undermines the author or brand in the eyes of the reader. After all, if you can’t be consistent and clear in your communication, what else might you be overlooking? Depending on the audience, project, or brand you’re proofing for, it’s best to stick to or develop a house style.

Be aware of structure.

In an ideal world, this is something a copyeditor should be taking care of. As many proofreaders will know, we don’t live in an ideal world.

Even the best pieces of writing have the potential to contain some kind of structuring error. Points dropped in paragraph four and picked up again in paragraph twelve after a digression that easily could have been its own section. Needless repetition of the same points over and over. Improper use of the inverted pyramid structure in news articles or press releases. In the case of scriptwriting, maybe even plot devices placed at strange beats that throw off the flow of a narrative, making it take longer than necessary to get from one act or scene to the next.

Regardless of the kind of structural issue, a top proofreader should be aware of the structure of a piece and be ready to make creative or logistical suggestions – even if they are ignored sometimes.

Plan focussed proof passes.

While two proofing passes are the absolute minimum, there’s no limit to how many a proofreader should commit to as standard. My golden rule is two-to-three standard passes and as many focussed or themed passes as you feel you need.

What do I mean by a ‘focussed pass’? A reading that concentrates on one specific type of category or error. This is done best with your error list by your side. Run through your list and perform quick scan passes – or even full document searches, if you’re using your computer or laptop – for each of the most common errors you’ve found.

By doing this, you give yourself a little peace of mind that you’ve done everything you can to rid the text of the kinds of mistakes most likely to drag it down.

Embrace software support.

If you’re using a computer, tablet, laptop, or other digital machine to write and proof a text (let’s face it, you probably are), take full advantage of the spellchecker tools available to you. Microsoft Office, Google Docs, LibreOffice, and Open Office word processors all have built in spellchecker tools that, despite having their weaknesses, are pretty solid. Most creative writing software does too.

Don’t feel like you’re too good for spellcheck. If you know a rule or spelling that it doesn’t, teach it. You never know what it’s going to find that you might accidentally gloss over.

Grammarly is also pretty great and free. One fun element of Grammarly, for the analytics nerds among you, is that it sends you a productivity report each month with breakdowns of common issues and overall wordcount – I’m at about 1-1.5 million words per year on average!

Pro tip: If you’re proofing within an Excel or spreadsheet doc, copy and paste the content over to Word (or similar) for a final spellcheck. For some reason, possibly because the developers just don’t expect writers to work in them, the spellcheck tools in spreadsheet software are much more scaled down compared to full-scale word processing software and so may not pick up on grammar, syntax, or structuring issues.

Ask a friend or colleague for help.

Common sense, right? A fresh pair of eyes are far more likely to spot those small errors that you’ve become blind to from simply looking at the text too much.

Worried that your helper might not have enough subject knowledge to give your text a thorough reading? That’s actually a strength. Someone with no experience in a text’s subject matter can tell you if terms or concepts that seem obvious to you might not be so obvious to everyone else.

Be mindful of inclusivity and cultural linguistic idiosyncrasy.

This stands true for text of any kind, but especially so for text that’s been translated from another language. The English language is unique in that it isn’t as gendered as some of the Romance languages. In Spanish, Romanian, Italian, French, or even German (which isn’t a Romance language), you could have a masculine table, a feminine cat, a masculine forest, a feminine moon, etc. For English speakers, the very concept of that can be mindboggling.

Personally, I’ve found that when proofing Russian-to-English text, there’s a lot of needless gendering. Too much use of ‘he’ that could be a more inclusive ‘they’. As a proofreader, you need to be mindful of these elements that can make a text needlessly gendered or accidentally uninclusive. You goal should always be to ruthlessly root out any potential for someone to be made feel alienated by some silly grammatical element of your text.

Some grammarians will argue that ‘they’ shouldn’t be used as a singular third-person pronoun because, by its very nature, ‘they’ is a plural term and I’m therefore advocating for incorrect usage of the word. To that I’d say, language evolves and having ‘they’ as a gender-neutral third-person singular pronoun is a pretty relevant evolution. We didn’t have much use for the word ‘download’ in the Dark Ages either.

Did you know that the Wizards of the Coast team write their Dungeons & Dragons rulebooks with a primary focus on female pronouns? It’s a relatively small change in any text document but says a lot about the company’s intentions in developing an inclusive atmosphere for all its players.

Do not print the document, thank you.

In this day and age, there’s really no need to print a document for a proofreading pass. It’s a waste of paper and ink and there’s no real advantage in it that I can see at all.

If you find it too hard to concentrate proofing on your computer screen (and who could blame you, most computers are connected to this distracting little thing called the ‘internet’) or just prefer the feeling of a page in your hand that you can write on, proof with a tablet or phone with the WiFi switched off and a digital pen. You can still mark up the same notes while holding something tangible in your hand and you won’t be contributing to the heat death of the planet.

All environment shaming aside, proofing a print version of a digital document is totally counterproductive. Not only do you need to go back to the digital version to update all the notes and corrections you’ve come up with, you lose the added advantage of all the friendly, helpful software at your disposal too.

Thanks for reading my Proofreader’s Playbook. I hope you got something out of it to bring back to your proofreading practices at home or in your work. Did I leave out any gospel rules of proofing that you like to adhere to? I’d love to hear about them in the comments. If you’d like to work with a processional proofreader on your next essay, article, brochure, or academic work, drop me a line and let’s chat. I also offer a wide range of creative copywriting services.

Fun challenge for proofreaders: Can you find any common mistakes and errors in the article above? Test your skills and leave them in the comments. I’m sure they’re there, have fun finding them!

Let’s be social

Further reading

-

RT @raleighreports: Man arrested on suspicion of murdering woman in Limerick apartment https://t.co/zqkhsfvFUi via @limerickpost

-

I’ve heard it called many things, but ‘wild toileting’ is a new one in me.

-

RT @limerickpost: Death of woman in Limerick apartment is now a murder case - https://t.co/jbyp0UAELf https://t.co/6W3eK4JMfh